Sarah Taylor1,2, Reza Daniels1, Dominique van der Mensbrugghe3, Robert Davies4.

1 University of Cape Town, South Africa

2 Global Ocean Accounts Partnership (GOAP)

3 Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP), Purdue University

4 tralac

Key Messages

- Purpose and contribution. This study constructs a South African Ocean Economy Satellite Account (OESA) that is SNA-consistent, adapts lessons from international pilots to local data realities, and documents a stepwise compilation approach usable in similar settings.

- What an OESA does. Reorganises existing national accounts to identify the market-based ocean economy and report GDP-compatible indicators (gross output, intermediate consumption, GVA, employment, and trade where feasible).

- Scope used - three pillars. In-scope activities are: (i) on-water production (e.g., marine capture fisheries, offshore gas/diamonds); (ii) coastal-dependent activity (e.g., beach/coastal tourism); and (iii) for-ocean-use goods/services produced anywhere but intended for use at sea (e.g., ship and boat building).

- Established sectors first. Benchmark studies should prioritise covering living resources, marine transport, marine/coastal construction, ship and boat building, minerals, and coastal tourism, anchored to the Supply–Use Tables.

- Handling mixed industries. Apply documented ocean economy partials (share estimates) where SIC classes combine ocean and non-ocean activity. Shares are reconciled to the Supply- Use table (SUT) to avoid double counting and maintain consistency.

- Administrative sources fill gaps. Because fine level SIC data are not always available, compilers use audited/administrative series to identify ocean shares transparently. Examples include sector yearbooks and registries (e.g., fisheries/aquaculture), infrastructure operator accounts (e.g., ports, utilities), budget and expenditure reports (transport/maritime agencies), and customs/business register data.

- Sector-specific workarounds are viable for data gaps but must be transparent. Pragmatic fixes (such as full allocation for shipbuilding pending a recreational split, using system-wide operator accounts for ports, participation proxies for coastal tourism, mine-count proxy for offshore diamonds) let compilation proceed despite data gaps, but they affect results, especially GVA, so documenting assumptions and limits is essential.

- Timeliness. Triangulating multiple sources with non-aligned reference years lengthens production lags relative to the core national accounts; a benchmark-year account, staged releases, and a clear revision policy improve usability.

- Core sequence, modular extensions. The core steps (scope, mapping, ocean shares, indicators) are sequential; extensions (trade tables, factor-income detail, additional partials, spatial refinements) are modular and added as evidence and capacity permit.

- Transferability. The approach is applicable to capacity-constrained contexts: start with a reconciled core, make assumptions explicit, and iteratively expand as more granular data become available.

Introduction

South Africa, with its extensive coastline and diverse marine sectors, is well-positioned to benefit from the development of an Ocean Economy Satellite Account (OESA). An OESA is a specialised extension of the national accounts that reorganises existing statistics to identify the market-based contribution of ocean-related activity (GOAP, 2024). It reports standard macroeconomic indicators, including gross output, intermediate consumption, gross value added (GVA), employment, and, where possible, trade, so that the ocean economy can be analysed alongside the rest of the economy on a comparable basis.

In the South African context, the ocean economy spans established marine industries and activities with clear ocean dependence: living resources (marine capture fisheries and marine aquaculture), marine transport (sea and coastal freight/passenger and port-related supporting services), marine and coastal construction (ports, shoreline infrastructure and coastal civil works), ship and boat building, marine minerals (offshore natural gas and diamonds; coastal mineral extraction in littoral zones), and coastal tourism and recreation (beach-linked expenditure and related services). The country also has the statistical assets needed to support an OESA, most notably the Supply–Use Tables (SUTs), and accessible administrative sources that can be used to estimate ocean shares where SIC classifications are too aggregated.

Against this backdrop, the contribution of this paper is threefold: first, it constructs a South African OESA that produces Gross Domestic Product (GDP) compatible measures of ocean-linked activity; second, it adapts lessons from international pilots to South Africa’s data context; and third, it documents a stepwise compilation method that other countries with similar data capacities can apply and refine.

Methodological Overview: Stepwise Framework for Developing an OESA

To guide the South African application, this subsection briefly summarises the stepwise methodology established in OECD’s Blueprint for Improved Measurement of the International Ocean Economy (Jolliffe et al., 2021) and the Global Ocean Accounts Partnership technical guidance document (GOAP, 2024), among others. The core sequencing and decision points will be summarised to ensure the OESA remains System of National Accounts (SNA) consistent, transparent, and reproducible across contexts. Notably, this study goes beyond the current valuations of the South African ocean economy (Hosking et al., 2014; Hosking et al., 2022) as solely offshore activity. This study uses the approach suggested by Colgan et al. (2013) to extend the boundaries of the ocean economy to represent the reliance and use of nearshore coastal resources in the economy to tackle the issue of misrepresenting and undervaluing the ocean economy.

The approach is grounded in the SNA and follows the satellite-account tradition: reorganising existing national accounts and carefully isolating the ocean component of mixed industries so results remain comparable with the core economy. The study adopts a pragmatic and evidence-led sequence, defining scope, classifying activities, selecting the accounting frame, estimating ocean shares (via direct attribution or documented “partials”), compiling core indicators, integrating data sources, and validating results. Throughout, the emphasis is on clarity, consistency and reproducibility, so that estimates can be updated as finer data become available and to ensure results are comparable with other national OESA.

The development of an OESA involves the following key steps:

i) Define the Scope of the Ocean Economy

ii) Classify Ocean-Related Economic Activities

iii) Select the Accounting Framework

iv) Estimate the Ocean Economy Share

v) Compile Core Indicators

vi) Ensure Data Integration and Consistency

vii) Validate and Interpret Results

Defining the Scope of the South African Ocean Economy

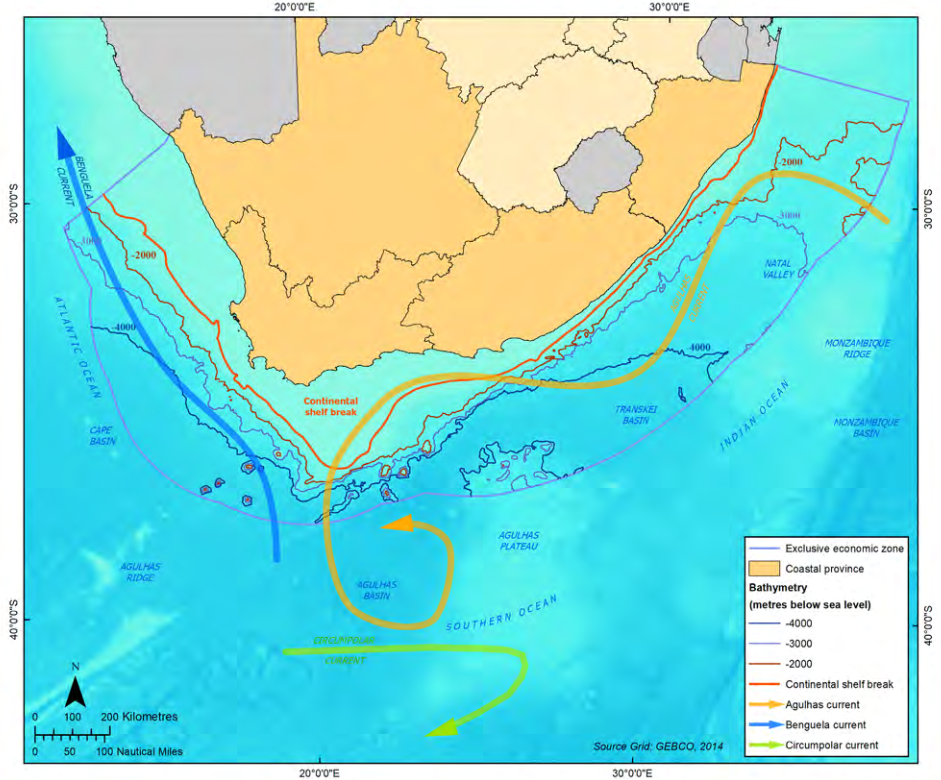

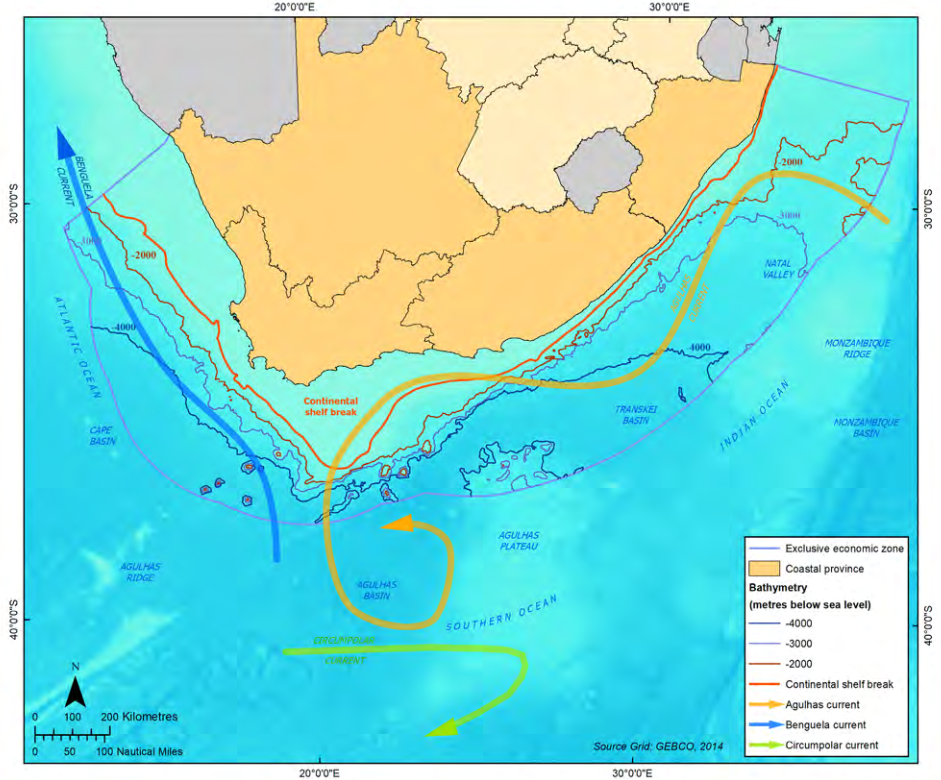

The starting point for compiling ocean economy statistics is the determination of the scope of the ocean economy. This includes geographical and economic production boundaries. In the South African context, the geographical scope of the OESA encompasses all national marine territories, including the country’s oceans and marginal seas (Figure 1). This comprises the Indian, the Atlantic, and the Southern Oceans within the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The ocean and coastal zones under South Africa’s jurisdiction are larger than the size of the country’s land territory and are highly productive areas displaying rich biodiversity (DFFE, 2021).

Source: DFFE, 2021

The ocean economy is defined to include all South African oceans but also includes ocean-related production that occurs away from this geographically defined area. The scope of the OESA includes ocean-related production within three categories (Colgan, 2013). The first category is production from the waters that are geographically within scope. This includes any production that takes place on the ocean or production that received essential inputs from the ocean, such as offshore oil and gas extraction and commercial fishing. The second category includes production that takes place near the ocean such as coastal recreation. The third category includes commodities purchased for use on the ocean regardless of where production takes place, such as ship and boat building.

There are many ocean industries including well established industries, such as capture fisheries and shipping, and emerging industries, such as marine biotechnology. Countries use different taxonomy and levels of aggregation which emphasises the complexity of creating internationally comparable sets of economic ocean accounts. To address this issue, this section focuses on identifying and measuring the major activity groupings advised as a starting point for the creation of the OESA based on similar work produced in the United States (U.S.) and Norway (Nicolls et al., 2020; Ånestad, & Nickelsen, 2022). The ocean economy activity groups considered in scope of this assessment are:

• Living resources, marine

• Minerals

• Ship and boat building, nonrecreational

• Tourism and recreation, coastal and offshore

• Construction, coastal and marine

• Transportation and warehousing, marine

The relevant products and industries from the South African SUTs have been mapped to these activity groups in Table 1. The activities can be seen as a basket of goods and services that are related to a certain type of activity in the OESA.

Table 1: Mapping South African Supply and Use Tables to Ocean Economy Activities

| Item | Activity |

|---|

| Fish | Living Resources |

| Prepared Fish | Living Resources |

| Crude petroleum, gas | Minerals |

| Metal ores | Minerals |

| Stone, sand, clay | Minerals |

| Other minerals | Minerals |

| Basic Iron, steel | Minerals |

| Basic precious metals | Minerals |

| Plaster, lime, cement | Minerals |

| Clay products | Minerals |

| Ship and Boat Building and Repair | Ship and Boat Building |

| Accommodation | Tourism and recreation |

| Food serving services | Tourism and recreation |

| Recreational, cultural | Tourism and recreation |

| Museums | Tourism and recreation |

| Entertainment | Tourism and recreation |

| Site preparation | Construction |

| Civil engineering | Construction |

| Building Installation | Construction |

| Building Completion | Construction |

| Equipment | Construction |

| Water transport | Transportation and warehousing |

| Supporting transport activities | Transportation and warehousing |

Calculating the Ocean Share of an Industry

Having defined the in-scope ocean activities and mapped South Africa’s SUT industries to these groupings, the next step is to quantify the ocean-related share within each mapped industry so that results remain consistent with the national accounts. Data were collected from Statistics South Africa (StatsSA), other governmental publications, and publicly available industry information. Aggregated industry data were the only national statistics available at the time of this study, meaning that most information was only available for second level SIC. Due to this, partial estimates (referred to as “partials” from now on) were needed to disaggregate to a level where marine related activities could be separated from non-marine. This study acknowledges that lower SIC level data may be available within StatsSA. Lower SIC level data should be used if the OESA is replicated in future, to ensure greater accuracy of the industry valuations. It is recommended to group data as shown in Table 2 to ensure consistency with other pilot studies for comparative purposes.

Table 2: Disaggregated SIC data for Future Ocean Economy Satellite Accounts

| Ocean Good and Service sub-themes | Industries linked to Ocean Use | Examples of disaggregated SIC defined industries (7th edition) |

|---|

| Living resources | Fishing, collecting seaweed, aquaculture | Marine Fishing (03110), Marine Aquaculture (03210) |

| Marine minerals | Mining the seabed for fossil fuels (crude oil and natural gas), other minerals, building materials and salt | Extraction of crude petroleum (06100), Extraction of natural gas (06200), Other quarrying of stone, sand, and clay (08109), Mining of phosphates (08991), Mining of diamonds (08991), Extraction of salt (08930) |

| Marine construction | Ocean related construction | Construction of buildings (4100), Civil Engineering (4200), Specialised construction activities (4300) |

| Ship and Boat Building and Repair | Ships, boats, and other transport equipment | Building of ships and floating structures (30110), Building of pleasure and sporting boats (30120), Repair of transport equipment, except motor vehicles (33150) |

| Marine transport | Ship, boat, and pipeline transport services | Sea and coastal passenger water transport (50110), Sea and coastal freight water transport (50120) |

| Marine tourism | Rental and other services to support access to the ocean’s composite services (not included under construction), including all recreational purchases | Accommodation (div 55), Real estate activities (div 68), Travel agency, tour operator, reservation service and related activities (div 79), Sports activities and amusement and recreation activities (div 93), Recreational beaches activities (93290) |

Data on the percentage of the industry relating to marine activities or marine resources were available for living resources, mining, tourism, and transportation. However, little information was available for the boat building industry and construction industry. Therefore, data from the 2018 SUT, industry information, and best conservative estimates were used to calculate ocean industry partials. A summary of the South African ocean economy partials calculated and used within this study are shown in Table 3. The Red-Amber-Green (RAG) column indicates confidence per partial, reflecting source quality, data vintage, and alignment with SIC scope. Green indicated high confidence (direct, recent evidence), amber is moderate (credible proxies/assumptions), and red indicates low (sparse evidence); the rating reflects reliability and should prioritise future work to strengthen lower-confidence partials.

Table 3: Summary of South African Ocean Economy Partials Used

| Ocean Economy Group | Industry | Mapped to SIC 7th Edition | Ocean Economy Share (Partial) | RAG Rating |

|---|

| Living Resources | Aquaculture | Group 032 | 0.86 | Green |

| Living Resources | Fishing | Group 031 | 0.997 | Green |

| Marine Minerals | Petroleum | Group 061 | 0.989 | Amber |

| Marine Minerals | Metal Ores | Group 072 | 0.174 | Amber |

| Marine Minerals | Stone | Group 081 | 0.174 | Amber |

| Marine Minerals | Non-Metallic Minerals | Division 07 | 0.138 | Amber |

| Marine Minerals | Iron and Steel | Group 071 | 0.174 | Amber |

| Marine Minerals | Other Mining and Quarrying (incl. diamonds) | Group 0899 | 0.174 | Red |

| Marine Construction | Site Preparation | Division 43 | 0.378 | Amber |

| Marine Construction | Civil Engineering | Division 42 | 0.3 | Amber |

| Marine Construction | Building Installation | Division 43 | 0.378 | Amber |

| Marine Construction | Building Completion | Division 43 | 0.378 | Amber |

| Marine Construction | Equipment | Division 43 | 0.378 | Amber |

| Ship and Boat Building and Repair | Building of Ships and Boats | Group 301 | 1.0 | Green |

| Marine Transport | Water Transport | Division 50 | 1.0 | Green |

| Marine Transport | Supporting Transport Activities | Division 52 | 0.2 | Amber |

| Marine Tourism | Hotels | Group 551 | 0.196 | Amber |

| Marine Tourism | Restaurants | Division 56 | 0.196 | Amber |

| Marine Tourism | Entertainment | Division 93 | 0.196 | Amber |

| Marine Tourism | Museums | Division 91 | 0.196 | Amber |

| Marine Tourism | Recreational Activities | Division 93 | 0.196 | Amber |

Living Resources

The fisheries industry in South Africa, as classified under SIC Division 03, is disaggregated from the broader category of agriculture, hunting, forestry, and fishing. Within Division 03, Group 031 covers inland, ocean, and coastal fishing, while Group 032 includes fish hatcheries and fish farms. Importantly, Group 031 includes the processing of fish, crustaceans, and molluscs carried out aboard fishing vessels, whereas shore-based or industrial fish processing is categorised separately under Group 102 “Processing and preserving of fish and fish products.” This delineation is critical for accurately capturing the marine-specific component of fisheries activity within the national accounts framework. Maintaining the boundary between Group 031 (capture fishing, including on-board processing) and shore-based industrial processing is essential to the statistical integrity of the account. Allocating primary production at sea to Group 031 and secondary transformation on land to Group 102 precludes double counting of output and value added, enables a clean separation of marine from inland/freshwater activity when estimating ocean shares, and preserves supply–use identities by aligning industry-specific inputs and outputs with the appropriate production boundary. The result is more defensible estimates of marine GVA and employment and improved comparability with other OESAs that observe the same primary–secondary distinction.

The fisheries sector itself comprises three primary subcomponents: commercial, recreational, and subsistence fisheries (DEFF, 2020). Commercial fishing overwhelmingly dominates the industry in economic terms, targeting high-value marine species such as hake, sardine, and anchovy (DAFF, 2016). While the sector’s direct contribution to national GDP is relatively modest, its socio-economic importance is substantial, particularly in coastal communities with limited employment alternatives (Isaacs, 2019). Inland fisheries, by contrast, are of negligible economic significance. There are no commercially viable inland fisheries in South Africa (FAO, 2010), and no official national estimates exist for the economic value of inland capture fisheries (Hara et al., 2021). However, FAO (2023) provides a detailed exploration of the marine capture fisheries sector, estimating that marine capture fisheries account for the majority of total output: 99.7% of national capture production, 98.6% of exports, and 96.1% of fish consumption (FAO, 2023).

For valuation purposes, this study undertook the disaggregation of aquaculture into freshwater and marine components. Using the Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries (DEFF) Aquaculture Yearbooks (2018–2020), species-level production volumes were assigned to freshwater aquaculture. Freshwater aquaculture includes species such as rainbow trout, tilapia, catfish, and ornamental fish, while marine aquaculture comprises commercially significant species such as abalone, oysters, mussels, and prawns, as well as finfish like dusky kob and yellowtail (Adeleke et al., 2021). The DEFF Aquaculture Yearbooks provided species-level production volumes, allowing for a spatial and taxonomic distinction between inland and marine-based activities. An assessment of the aquaculture sector’s total value over multiple years reveals a consistent dominance of marine-based production, with inland aquaculture accounting for only 12% to 14% of the sector’s total value across the period. Given the near-total dominance of marine-based capture and the relatively small scale of freshwater aquaculture, the ocean-related portion of the fisheries industry could be estimated with a high degree of confidence.

Marine Minerals

To estimate the ocean economy’s share of South Africa’s mining sector, a combination of SUT data and Annual Financial Statistics (AFS) from StatsSA was employed. While the national accounts data offer only aggregated mining figures, the AFS provided further disaggregation by mining sub-sector, enabling a more refined assessment of marine-relevant activities. Following the definitional criteria of the ocean economy outlined by Colgan (2013), which includes both activities occurring directly on ocean waters and those geographically dependent on coastal proximity, the analysis sought to isolate mineral extraction linked to offshore as well as coastal environments.

The methodology involved a spatial assessment of mineral resource extraction sites, using the Operating Mines, Quarries and Mineral Processing Plants in South Africa directory (DMRE, 2022) to identify active mines and their locations. Particular focus was placed on marine natural resources, namely offshore diamonds and natural gas, as well as coastal mineral deposits such as granite, slate, and limestone, which are economically significant and located in coastal zones. For natural gas, production figures were sourced to distinguish the contribution of offshore fields, such as the F-A Field and South Coast Complex, which account for the majority of national output (U.S. EIA, 2022). These data enabled a production-weighted estimate of the ocean economy share for the natural gas sub-sector.

In contrast, for offshore diamond mining, the absence of production-level data necessitated the use of mine counts to estimate the ocean partial. Specifically, the proportion of listed offshore diamond mines to the total number of diamond mines was applied as a proxy for marine contribution. While this approach offers a practical interim solution, it assumes uniform output across all mining operations, which is an assumption that may distort the valuation and should be revisited in future iterations. The use of mine counts rather than production values is therefore acknowledged as a methodological limitation.

Beyond these offshore resources, the analysis also considered coastal minerals whose deposits are geographically concentrated along the shoreline. These include dimension stone (such as granite and slate) and limestone, which are extracted in coastal regions and contribute meaningfully to local economies. Inclusion of these resources aligns with the broader interpretation of ocean-linked activity, acknowledging the economic dependence of certain mineral sub-sectors on coastal geography.

Given the limitations in publicly available production data and the general nature of mine location records, this study adopted a pragmatic approach by applying coastal mine ratios based on location within coastal municipalities. The coastal zone was defined operationally as cities or towns situated directly along the South African shoreline. While this spatial proxy provides a starting point for partial estimation, it underscores the need for more granular spatial and production-level data to improve precision. Future methodological improvements should focus on refining spatial attribution techniques and accessing company-level data to enable a more accurate allocation of economic value between marine and non-marine components of the mining sector.

Marine Construction

Estimating the ocean economy share of South Africa’s construction sector presents methodological challenges due to the absence of explicit data disaggregating coastal and inland activity. Unlike sectors with direct marine linkages, construction spans a broad range of inland and coastal infrastructure and is not inherently tied to ocean proximity in national statistics. Considering this, a partial ocean estimation approach was adopted, drawing on multiple complementary data sources to approximate the spatial distribution of construction activity. The SUTs provided the overall industry value for construction, which, although aggregated, served as the foundational basis for estimating the ocean-related share. The construction sector in the SUTs is disaggregated into key components, including site preparation, building of complete constructions or parts thereof and civil engineering, building installation, building completion, and the renting of construction or demolition equipment with operators, all of which were considered in the partial calculation process. Further, a publication on Selected Building Statistics of the Private Sector (StatsSA, 2019) was used to assess completed buildings and approved building plans by municipality, with provincial aggregation enabling the approximation of construction activity shares attributable to coastal regions.

Infrastructure development reports from agencies such as the South African National Roads Agency (SANRAL) and municipal planning departments provided insight into large-scale development projects, while urbanisation and population density data were used to identify areas experiencing the most rapid growth. These spatial trends were supplemented by geographic overlays from environmental datasets, including maps of protected and conservation areas, which influence where construction can legally and practically occur. Additionally, Special Economic Zones (SEZs) situated in coastal regions were identified as focal points of construction due to their industrial and export-oriented development incentives. While no single source provided a definitive answer, the combination of these varied data inputs (StatsSA and SANRAL reports) enabled a reasoned estimation of the coastal share of construction activity, which proved to be a necessary methodological adaptation when valuing ocean-partial sectors in data-constrained contexts.

Ship and Boat Building and Repair

The ship and boat building industry, classified under SIC Group 301, includes the construction of commercial vessels, naval ships, and recreational boats. South Africa’s geographic positioning along major international shipping routes and growing expertise in niche markets such as high-speed or custom-designed vessels positions the sector for expansion, though it faces constraints from global competition, infrastructure limitations, and skills gaps (SAMI, 2020; Suttie, 2021). The central measurement challenge is that the national accounts aggregate ocean- and inland-use vessels in a single class, while the datasets required to split them (such as detailed registration, licensing, or end-use evidence) are not available at sufficient granularity.

However, based on the structural characteristics of the industry and the known dominance of coastal applications, particularly for shipbuilding and larger-scale recreational and commercial vessels, this study assumes a 100% allocation of the industry’s value to the ocean economy. While this assumption introduces some inaccuracy, it is consistent with the observation made by Statistics Norway (Ånestad et al., 2022), which noted that in cases where a product meets sufficient definitional criteria of ocean dependency or where disaggregation is not feasible, it may be treated as fully marine for valuation purposes.

Experience from the U.S. illustrates an alternative classification choice rather than a different share. U.S. accounts separate recreational vs. non-recreational boat building and place the former under tourism and recreation rather than under shipbuilding (Nicolls et al., 2020). South Africa’s current data do not permit this reallocation; therefore, all of SIC 301 remains in ship and boat building in this OESA. This aggregated treatment does not alter the overall measured size of South Africa’s ocean economy; it affects only the distribution across activity groupings. That said, the presence of pleasure and sporting boats (SIC 30120) highlights a distinct, future refinement task, one that is conceptually separate from the marine-versus-inland share problem. As improved evidence becomes available (such as verifiable vessel-use registers), two upgrades are recommended: (i) a marine vs. inland split where warranted, and (ii) a recreational vs. non-recreational reallocation to align with international practice.

In sum, although the assumption of full inclusion may marginally overstate the marine component of the industry, it is methodologically defensible, and consistent with practice elsewhere, given the sector’s alignment with ocean-facing policy objectives and the lack of inland shipbuilding activity of comparable scale. Nevertheless, efforts to refine this valuation through better data on vessel type, use, and location of deployment would enhance the accuracy of future OESA.

Marine Transportation

Ocean related transportation is located within the transport, storage, and communication category in South African national accounts. There is disaggregation down to water transport (SIC Division 50) which includes sea and coastal water transport (Group 501) and inland water transport (502). Sea and coastal water transport comprises coastal shipping and ocean shipping. Inland water transportation is very limited due to South Africa’s geographical and hydrological characteristics. Most of the rivers are not suitable for commercial inland transportation due to their seasonal nature and variable flow rates (Grenfell and Ellery, 2009; StatsSA, 2017).

The aggregated supporting and auxiliary transport activities (SIC Division 52) include cargo handling, storage and warehousing, parking, salvaging of distressed vessels and cargoes, maintenance and operation of harbour works, lighthouses, operation of airports, flying fields and air navigation facilities, and operation of roads and toll roads. Transnet is the statutory operator of South Africa’s ports. Transnet’s financial statements (Transnet SOC Ltd., 2018) were used to estimate the marine transport portion of supporting and auxiliary transport activities. However, the financial statements do not explicitly itemise maritime transport maintenance costs. As an alternative data source for the proportional allocation analysis of South Africa’s maritime transport expenditure, data were obtained from Vote 35 on Transport in the Estimates of National Expenditure (ENE) 2019 (National Treasury, 2019) which itemise maritime transport expenditure. Future improvements would benefit from the development of more detailed transport statistics that clearly delineate marine-specific services within broader transport infrastructure categories.

Tourism and Recreation

The partial valuation of South Africa’s tourism sector within the ocean economy focused specifically on coastal and beach-related tourism, given its direct connection to marine environments. While tourism contributes significantly to national GDP and regional development, particularly in coastal provinces, available data lacked sufficient geographic detail to separate precisely coastal from inland tourism expenditure within coastal provinces. To address this, the ocean economy share was estimated by applying the percentage of both domestic and international tourists who reported engaging in beach-related activities to total tourism expenditure, as reported by South African Tourism (2019). This proxy assumes proportional spending by beachgoers and treats their expenditure as coastal-dependent. Although this method may underestimate the total marine-related tourism value, excluding activities such as coastal nature reserve visits, it offers a conservative and methodologically transparent estimate. Tourism-related industries were captured using relevant SUT classifications including accommodation, food services, and recreation. Further refinement would require more granular, spatially disaggregated tourism data.

South African Ocean Economy Satellite Account

The methodology to calculate the figures in the South African OESA (Table 5 to 9) followed international best practice summarised in Taylor et al. (2025). The indicators measured in the OESA are output, intermediate consumption, compensation of employees, and GVA. Information was drawn from the 2018 SUT and Social Accounting Matrix (SAM) to measure group and total economy economic contributions. This OESA defines the ‘ocean economy’ as a selected set of established marine sectors, in line with pilot-study recommendations for a practical starting point (Nicolls et al., 2020). As such, it does not capture the full breadth of South Africa’s ocean economy; emerging sectors will need to be added in future iterations.

Gross output, reported in Table 5, is a measure of sales that captures the total value of goods and services produced by an economy. It includes sales to final users (GDP) and sales of intermediate inputs to other industries (Nicolls et al., 2020). In 2018, total gross output in the South African ocean economy amounted to R393.3 billion. A large share of this production is absorbed as intermediate consumption - the value of goods and services consumed as inputs in the production process during the accounting period, excluding fixed assets (European Commission et al., 2009) – which reached R260.8 billion in 2018 (Table 6). Labour remuneration forms another major component of the ocean economy, with compensation of employees totalling R71.2 billion in 2018 (Table 7).

Table 5: 2018 Output, by group (R’million; basic prices; annual)

| Group | Living Resources | Marine Minerals | Marine Construction | Ship and Boat Building and Repair | Marine Transport | Marine Tourism | Total |

|---|

| Ocean Economy Portion | 20,255.98 | 142,769.10 | 135,413.70 | 5,555.00 | 43,430.45 | 45,840.97 | 393,265.20 |

Table 6: 2018 Intermediate Consumption, by group (R’million; basic prices; annual)

| Group | Living Resources | Marine Minerals | Marine Construction | Ship and Boat Building and Repair | Marine Transport | Marine Tourism | Total |

|---|

| Ocean Economy Portion | 9,772.06 | 96,858.93 | 94,801.62 | 4,975.00 | 27,652.34 | 26,710.88 | 260,770.83 |

Table 7: 2018 Compensation of Employees, by group (R’million; basic prices; annual)

| Group | Living Resources | Marine Minerals | Marine Construction | Ship and Boat Building and Repair | Marine Transport | Marine Tourism | Total |

|---|

| Ocean Economy Portion | 3,535.059 | 22,119.19 | 28,152.04 | 898.00 | 6,857.46 | 9,671.13 | 71,232.88 |

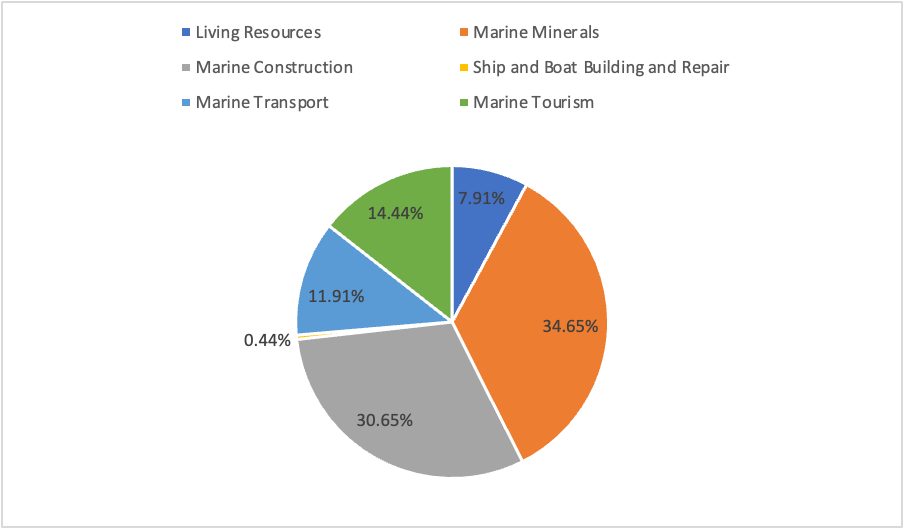

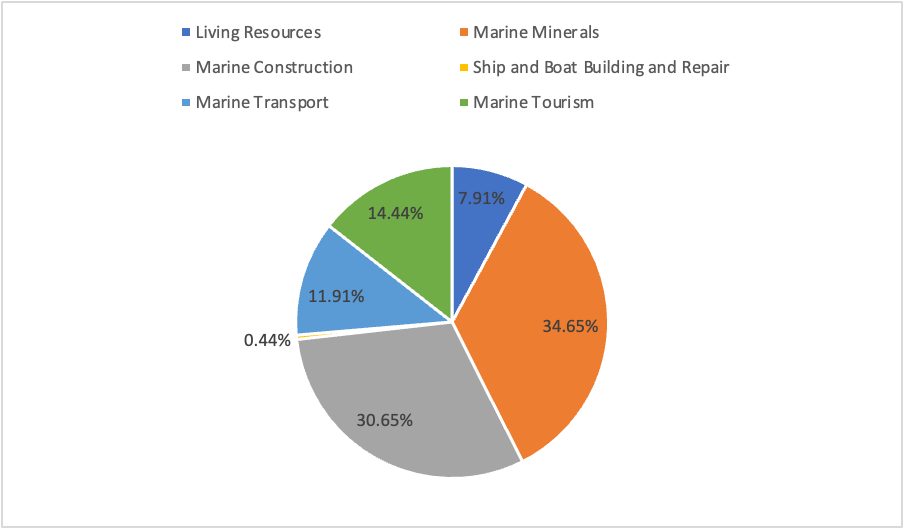

Value added is the portion of GDP created by an industry. It is the value of what the industry produces minus the value of the inputs it uses in production, and it can be measured as employee compensation plus taxes on production and imports minus subsidies, plus gross operating surplus (Nicolls et al., 2020). Of the total ocean economy GVA, the top contributor by group was marine minerals followed by marine construction (Figure 2). Looking wider to the whole economy, the ocean economy contributed 132.5 billion to current-rand value added (GDP) in 2018. The results of the study show that the ocean economy equates to 2.74% of South African GDP.

Value added represents the portion of GDP generated by an industry and is defined as the value of what the industry produces minus the value of the inputs it uses in production; operationally, it can be measured as employee compensation plus taxes on production and imports minus subsidies, plus gross operating surplus (Nicolls et al., 2020). Within the South African ocean economy, GVA is dominated by marine minerals and marine construction, which account for 34.65 and 30.65 per cent of total ocean GVA respectively, followed by marine tourism (14.44 per cent), marine transport (11.91 per cent) and living resources (7.91 per cent), while ship and boat building and repair contributes only 0.44 per cent (Figure 2). In the wider economy, the ocean economy generated R132.5 billion in current-rand value added (GDP) in 2018, equivalent to 2.74 per cent of South Africa’s GDP (Table 9).

Table 8: 2018 GVA, by group (R’million; basic prices; annual)

| Group | Living Resources | Marine Minerals | Marine Construction | Ship and Boat Building and Repair | Marine Transport | Marine Tourism | Total |

|---|

| Ocean Economy GVA | 10,484.69 | 45,910.30 | 40,612.11 | 580.00 | 15,777.80 | 19,130.19 | 132,495.09 |

Figure 2: Total South African Ocean Economy Value Added by Group

Table 9: South African Ocean Economy Portion of Total GDP 2018

| Indicator (2018 base year) | Total (R’million) |

|---|

| Ocean Economy Value Added | 132,495.00 |

| National Economy Total GVA | 533,500.99 |

| South Africa GDP | 4,829,603 |

| Ocean Economy % of Total GDP | 2.74% |

**Lessons for capacity-constrained compilers

(from the South African application)**

The following recommendations are aimed at national statistical offices and line ministries (such as fisheries, transport, minerals, tourism) working in data-constrained settings. They distil what mattered in the South African application and indicate what to prioritise first, what to document, and where to use administrative sources when SIC classifications and SUTs are not sufficiently disaggregated. The steps are sequential, but several enhancements are modular and can be phased in as data systems mature. A benchmark-year core can be established first with coverage extended iteratively, such as trade tables or additional information on partials, as evidence and capacity allow.

1. Start with established sectors and a core indicator set. Prioritise living resources, marine transport, minerals, ship and boat building, tourism, and marine/coastal construction, and compile the core aggregates (gross output, GVA, employment), extending only where the SUT can support balancing.

2. Use external sources when fine SIC detail is not available. Where official statistics are only available at aggregated SIC levels (as here in this study), external administrative sources (e.g., DEFF Aquaculture Yearbooks, Transnet statements, DMRE mine directories) are essential to estimate ocean shares transparently. Make the necessity explicit: the use of external sources follows directly from the lack of sufficiently disaggregated SIC data.

3. Document assumptions and reconcile to the SUT. Where mixed industries cannot be split cleanly, apply partials with published data sources and allocation rules. Keep totals reconciled to the SUT to preserve internal consistency and comparability across activities.

4. Be explicit about methodological limitations. In this study, for offshore diamonds, production-level data were unavailable. The study therefore used mine counts to proxy the marine share. This is a practical interim solution for output, but it is especially problematic for GVA because it implicitly assumes uniform productivity and cost structures across mines. Future iterations should replace mine-count proxies with production-weighted shares using company reports, regulatory returns, or microdata to improve GVA attribution.

5. Plan a staged data-improvement roadmap. Priorities include (i) product-level estimation to sharpen ocean/non-ocean identification, (ii) vessel-use registers to refine ship/boat building allocations, (iii) spatially disaggregated tourism statistics, and (iv) port-service detail (e.g., maintenance) to enhance supporting-services measurement.

6. Timeliness and triangulation. Compiling an OESA in data-sparse regions can require triangulating multiple sources with non-aligned release calendars and reference years. Compilers must make explicit time-alignment assumptions, which lengthens production lags relative to the core national accounts and can limit near-term monitoring. Mitigate by publishing a benchmark-year account with a clear revision policy, transparent alignment rules, and staged releases (core indicators first, followed by extensions as late data arrive).

Taken together, these lessons show that an OESA can be built and improved iteratively in data-constrained environments: begin with a narrowly defined, SUT-consistent core; use transparent partials and administrative sources where necessary; and upgrade methods as finer data become available. The resulting account is both policy-relevant for South Africa and informative for other developing countries seeking a workable, standards-aligned approach to measuring the ocean economy.

This study underscores the value of embedding OESA development within national planning and statistical ecosystems. Institutional collaboration, shared data infrastructures, and clearly defined methodologies are essential for scaling and sustaining ocean economy accounting. The South African OESA offers both a replicable model for other developing countries and a foundation for more economic ocean economy accounts in the future.

Conclusion

The development of South Africa’s OESA represents a significant step forward in measuring the contribution of marine-based industries to the national economy. Drawing on international experience, the study adopted a satellite accounting framework aligned with the SNA to provide GDP-compatible estimates of ocean-linked economic activity.

This study demonstrates that a credible, SNA-consistent South African OESA can be compiled with existing statistical assets, complemented by targeted administrative sources. Anchoring the compilation to the 2018 SUT and applying documented partials yields coherent estimates of gross output, intermediate consumption, and GVA for key ocean activity groups. The approach reflects international practice while being tailored to South Africa’s data realities

The OESA was compiled at the group (industry) level, focusing on the economic output of each group. This enabled the derivation of key economic indicators such as gross output, intermediate consumption, and GVA. However, future work could enhance this account by conducting estimates at the product level, which would allow for finer disaggregation and better identification of ocean-relevant goods and services. This approach would align with Portugal’s SAS approach (Statistics Portugal and Directorate-General for Maritime Policy, 2016). As more detailed data become available, particularly from business registers and geospatially tagged industry activity, refining the partial estimation methods will be critical to improving the precision and reliability of the OESA.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Global Ocean Accounts Partnership (GOAP) for support with design and layout of the working paper and for technical review provided by Philip James and Eliza Northrop. Any remaining errors are the authors’ own, and the views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of GOAP.

References

Adeleke, B., Robertson-Andersson, D., Moodley, G., & Taylor, S. (2020). Aquaculture in Africa: A Comparative Review of Egypt, Nigeria, and Uganda Vis-À-Vis South Africa. Reviews in Fisheries Science & Aquaculture, 29(2), 167–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/23308249.2020.1795615

Ånestad, K. and Nickelsen, E. (2022). Ocean satellite account: Description of methods and sources. Statistics Norway. ISBN 978-82-587-1523-5. https://www.ssb.no/en/nasjonalregnskap-og-konjunkturer/konjunkturer/artikler/ocean-satellite-account.description-of-methods-and-sources/_/attachment/inline/8c126fa0-31a3-4af0-a9f6-ea58affc51c2:07f96824a693253829ee08012e3938c1c8f47e61/NOT2022-17.pdf

Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). (2022). Marine economy satellite account, 2014–2020. Bureau of Economic Analysis. https://www.bea.gov/news/2022/marine-economy-satellite-account-2014-2020

Colgan, C.S. (2013). The ocean economy of the United States: Measurement, distribution, & trends. Ocean & Coastal Management, 71, 334–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2012.08.018

Department of Environment, Forestry, and Fisheries (2020). Aquaculture Yearbook 2018 South Africa.

Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism (2020). Annual Report 2019/2020. Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism, South Africa.

DFFE, 2021. National Data and Information Report for Marine Spatial Planning: Knowledge Baseline for Marine Spatial Planning in South Africa. Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment, Cape Town: South Africa. [https://www.dffe.gov.za/sites/default/files/docs/ndir_msp.pdf]

Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (2025). ‘Protected and Conservation Areas Database (PACA)’, Environmental Geographical Information Systems (E-GIS). Available at: https://egis.environment.gov.za/protected_and_conservation_areas_database_paca (Accessed: 11 January 2025).

Department of Trade, Industry and Competition (DTIC) (2025). ‘Special Economic Zones (SEZ)’, Industrial Financing. Available at: https://industrialfinancing.co.za/special-economic-zones-sez/ (Accessed: 11 January 2025).

DTIC (2020). Industrial Policy Action Plan 2020/21 – 2022/23. Department of Trade, Industry, and Competition, South Africa.

European Commission, International Monetary Fund, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, United Nations & World Bank (2009). System of National Accounts 2008, United Nations, New York.

FAO (2010) National Fishery Sector Overview: South Africa. Available at: https://www.fao.org/fishery/docs/DOCUMENT/fcp/en/FI_CP_ZA.pdf

Global Ocean Accounts Partnership (2024). Technical Guidance on Ocean Accounting for Sustainable Development. Centre for Sustainable Development Reform.

Grenfell, S.E., Ellery, W.N. (2009). Hydrology, sediment transport dynamics and geomorphology

of a variable flow river: The Mfolozi River, South Africa. Water SA Vol. 35 No. 3.

Hosking, S., Du Preez, V. Kaczynsky, J. Hosking, M. Du Preez & R. Haines (2014) The Economic Contribution of the Ocean Sector in South Africa, Studies in Economics and Econometrics, 38:2, 65-82, DOI: 10.1080/10800379.2014.12097268

Hosking, S., Mtati, O. (2022) Why and how to measure the contribution of South Africa’s ocean economy. ERSA Working Paper 882.

Isaacs, M. (2019). Governance reforms and small-scale fisheries identity in South Africa. Maritime Studies, 18(3), 303–318.

Jolliffe, J., C. Jolly and B. Stevens (2021), “Blueprint for improved measurement of the international ocean economy: An exploration of satellite accounting for ocean economic activity”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, No. 2021/04, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/aff5375b-en.

Nicolls, W., Franks, C., Gilmore, G. et al. (2020). Defining and Measuring the U.S. Ocean Economy. https://www.bea.gov/system/files/2021-06/defining-and-measuring-the-united-states-ocean-economy.pdf

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2016). The Ocean Economy in 2030. OECD Publishing. https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264251724-en

Statistics South Africa (2019). Selected building statistics of the private sector as reported by local government institutions. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P50411/P50411December2019.pdf (Accessed: 24 Aug. 2024).

Suttie, M. (2021). The future of South African shipbuilding: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Maritime Affairs, 19(2), 134–149.

Taylor, S., Daniels, R., van der Mensbrugghe, D., Davies, R. (2025). Valuing the ocean economy: lessons from earlier adopters [Working Paper], Global Ocean Accounts Partnership. Available at: /publications/valuing-the-ocean-economy-lessons-from-earlier-adopters

Transnet SOC Ltd. (2018). Annual Financial Statements for the year ended 31 March 2018. Johannesburg: Transnet. Available at: https://static.pmg.org.za/Transnet_AFS_2018.pdf.17.08.pdf

U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) (2022). Country analysis executive summary: South Africa, U.S. Energy Information Administration. Available at: https://www.eia.gov/international/content/analysis/countries_long/South_Africa/pdf/south_africa.pdf