Why ocean data must include people

Rachel Thoms, Rebecca Shellock and Philip James

Coastal communities remain largely invisible in ocean policy decisions, yet they hold centuries of knowledge about ocean resources and depend entirely on marine ecosystems for their livelihoods and wellbeing. A new eight-country analysis reveals that countries have the tools and data to start integrating social data into Ocean Accounts transforming ocean governance into an instrument of equity. The findings partially counter the common assumption that incorporating social dimensions requires costly new data collection programs that delay or prevent implementation.

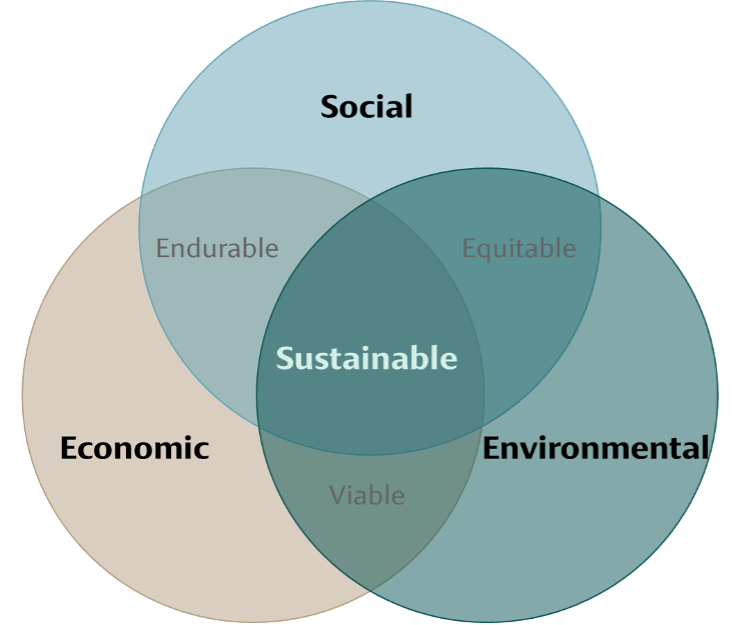

For private sector investors and policymakers alike, Ocean Accounts offer a transformative framework to change this. As an integrated statistical framework that goes beyond traditional economic indicators to measure and manage progress toward ocean sustainable development, Ocean Accounts track natural ocean assets, the services they provide, and their links to economies and social wellbeing. This approach is gaining momentum globally, with countries and investors recognizing that traditional economic indicators fail to capture the true value of ocean resources, the sustainability of ocean-based activities, or the social and cultural dimensions that underpin thriving coastal economies.

At UNOC, 193 member countries agreed to the ‘critical need’ for ocean accounts and 19 signed a Pledge to “Advance Ocean Accounts for Ocean Sustainable Development by 2030”. The recently published High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy Handbook (Barzuna et al., 2025) for developing Sustainable Ocean Plans (SOPs) highlights the critical importance of data in developing an SOP and the need to integrate social concerns within the plans. This integration is essential not only for environmental sustainability but for ensuring that private sector engagement in the blue economy recognizes and protects the social-cultural value and stewardship roles that communities hold.

As countries prepare for the 30th annual United Nations climate change conference (COP30) in Brazil, integrating social data becomes critical to delivering on commitments spanning adaptation and local governance, health, jobs, education, justice and human rights, and the protection of workers and indigenous peoples whose knowledge and livelihoods depend on ocean stewardship.

To date, most Ocean Accounts developed by countries have focused primarily on economic and environmental data, missing the critical social dimension. A persistent argument in ocean governance is that insufficient social data is available and that we cannot move forward without more information. However, the reality is different.

An assessment by the Global Ocean Accounts Partnership (GOAP) and the World Resources Institute (WRI) explored national government data sources across eight countries (Mozambique, Belize, Vanuatu, Costa Rica, Fiji, Madagascar, Sri Lanka, and Maldives). The study identified 880 indicators held in national data systems which can be used to build Ocean Accounts that integrate social data (i.e. “Social Accounts”). This analysis reveals four key findings that should inform SOP and COP30 discussions while truly "leaving no one behind."

1. Strong foundations exist for integrating social data into Ocean Accounts

Substantial existing information is available that countries can immediately utilize to incorporate social data into the Ocean Accounts framework. This wealth of data stems from well-established national survey infrastructures, particularly Household Income and Expenditure Surveys (HIES), along with Labour Force Surveys and Population and Housing Censuses. The analysis identified 880 indicators spanning 17 types of social data from these existing sources that can be applied to Ocean Accounts. This highlights that there is a substantial amount of data that hasn’t been fully leveraged.

The gap is not always in data collection, but in how we organise, analyse, and integrate the data that already exists.

Hence, the tools and systems to develop robust Ocean Accounts which incorporates social data already exist. This will help to ensure that the social domain is integrated into ocean governance and policy decisions sooner rather than later. Countries can start small with existing data and begin building these accounts now, rather than waiting for perfect or comprehensive data systems or undertaking primary data collection. This integration will transform Ocean Accounts from technical measurement tools into instruments of equity, ensuring that national data systems reflect not just what the ocean provides economically, but who benefits, who bears the costs, and whose knowledge matters in shaping sustainable ocean futures.

2. There is considerable data on employment, income, poverty and livelihoods

Our analysis revealed that there is high availability of data on employment, income, poverty, and livelihoods, and moderate availability of data capturing human health, food security, and education. All eight countries have data which captures these dimensions. With high availability of employment, income, poverty, and livelihood data, plus moderate availability of health, food security, and education information, nations can start developing these comprehensive frameworks without waiting for lengthy primary data collection efforts. The significance is that this removes the "data desert" problem that often prevents countries from moving beyond basic social statistics to incorporating social data in Ocean Accounts.

This existing data provides a solid foundation to create an integrated picture of society's relationship with ocean ecosystems. The employment and income data can reveal economic dependencies on ocean resources, while poverty indicators help identify vulnerable populations. Health and education data contribute to understanding social resilience and adaptive capacity.

3. National data systems lack an ocean-lens

Our analysis found that the countries reviewed have developed detailed systems to measure the many factors that contribute to the wellbeing of their populations ranging from employment and food security to disaster risk. Yet, the role of ocean ecosystems and ocean economies remains largely hidden. Our analysis identified six gaps which currently limit the visibility of the ocean within national social data systems.

Coastal populations are underrepresented in surveys: Two-thirds of the indicators come from surveys that use a two-stage stratified sampling method. This approach works well for representing national populations or large regions, but it often leads to coastal areas being under- or unevenly sampled, making it hard to apply the observations to coastal populations more broadly.

There is a lack of marine-specific indicators and categorisations: Standard survey instruments frequently lack the granularity needed to distinguish marine from freshwater activities. Even when relevant data exists, it's often coded in ways that obscure ocean linkages. Additionally, most surveys capture only formal employment while missing the informal, seasonal, and subsistence activities that characterize many coastal livelihoods. For example, livelihoods connected to reefs, mangroves, or marine fisheries are lumped into broad economic categories, such as "Fish and Fisheries," making them hard to track beyond associations with broader aquatic systems.

There are limited spatial linkages: Fewer than half of the indicators could be linked to marine and coastal areas, either by directly referencing the habitats or features within marine environments (e.g. mangroves, estuaries, nearshore) or by including location data (e.g. GPS coordinates or mapped census areas) which can be used to analyze proximity to ocean ecosystems.

There is limited data disaggregation for marginalised groups: Surveys may not collect disaggregated data, but we also found that sampling frame design may actively excluded groups from being represented. Disaggregated data is rarely available for key groups including people with disabilities or Indigenous populations.

There are instances of exclusion of marginalised groups in sampling frames: Survey sampling frames may actively exclude entire groups from being represented in the first place. This occurs due to the omission of subsistence, informal, or female-dominated activities from survey design or collection methods, meaning these populations are systematically missed before data collection even begins.

Social and cultural dimensions are absent: The ocean is not only a source of jobs and income. It holds deep cultural, social, and spiritual value. But most national statistics reviewed don’t account for traditional knowledge, cultural identity, governance, or stewardship roles, leaving critical aspects that shape human-ocean relationships unmeasured.

4. There are six main ways to strengthen national data systems to make the ocean and its communities visible

Countries looking to include social data in ocean accounting don’t need to start from scratch. Most are already collecting a wide range of relevant data. Targeted adjustments to these systems can make the ocean and the people who depend on it more visible. To build robust Ocean Accounts, the report highlights six key shifts:

Boost coastal representation in survey design: Deliberately stratify populations across coastal and inland areas and oversample coastal areas where populations are small. When possible, design samples to reflect the geographic, ecological, and cultural diversity present along the coast.

Incorporate survey questions which record mixed livelihoods: Incorporate questions beyond "main jobs" to capture seasonal, informal, and subsistence activities and resource use. Agricultural surveys, used widely across the countries we reviewed, have untapped potential to capture diverse coastal resource use. While many have fisheries and aquaculture modules, they remain underdeveloped compared to those on crops and livestock.

Apply existing classification systems at a more granular level: Use more granular levels of existing classification codes or add additional sub-codes that differentiate between marine and freshwater systems (e.g., consumption category codes for “Reef fish” rather than two-digit codes for "Fish and other seafood") and train enumerators and coders to capture this detail.

Ensure social data has spatial linkages with coastal and marine habitats. Ensure that data can be linked to specific coastal and marine habitats. For example, questions could ask about different types of ecosystems people use (i.e. reef fishing versus seagrass fishing). Surveys could also be planned to cover different ecological zones, such as reefs, estuaries, or mangroves. Collect location data (like GPS points or mapped survey areas) so the information can be connected to these habitats.

Design surveys with disaggregation and inclusion in mind: Disaggregate indicators across social groups of concern. Adjust questionnaires, sample design, and collection methods to systematically include marginalized groups and underrepresented populations and activities. Ensure that Indigenous peoples and local communities have meaningful representation in decision-making processes that use this data.

Develop surveys which capture context-specific sociocultural indicators: Include broader measures of how people access, govern, relate to, and know the ocean. Avenues include targeted questions based co-created indicators or integrating qualitative and participatory data as well as Indigenous, Traditional and Local (ITL) knowledge systems within official data.

Transforming ocean governance through social data

Incorporating social data into Ocean Accounts will fundamentally reshape how coastal communities participate in and benefit from ocean governance. When data is disaggregated and analysed through an equity lens, it reveals disparities and inequalities that might otherwise remain hidden. This understanding becomes the first step towards creating targeted interventions and policies that promote fairness and address the root causes of social and environmental injustices.

For countries developing Sustainable Ocean Plans integrating social data within an accounting framework offers a practical, evidence-based method to ensure that economic opportunities genuinely benefit all coastal communities and reflect the true dependencies and vulnerabilities of those most reliant on ocean resources. This integration is essential not only for environmental sustainability but for ensuring that development recognizes and protects the social-cultural value and stewardship roles that communities hold. This is a commitment underscored by COP30's emphasis on human rights, indigenous affairs, and meaningful representation in decision-making processes.

By making marginalized groups visible in national data systems, this integration ensures that the voices of coastal communities, small-scale fishers, indigenous communities, and other marginalized groups directly influence the policies that affect their lives.

For communities on the ground, this means their knowledge and daily experiences with the ocean will finally count in macro-level decisions.

When governments can see exactly how ocean health affects local livelihoods, income, and food security and how benefits and burdens are distributed across different groups, they can design policies that protect both marginalized populations and marine ecosystems.

This will result in more accurate, legitimate ocean governance that delivers equity and justice. Communities will see their real dependencies on ocean resources reflected in national planning, ensuring that blue economy development enhances rather than threatens their well-being. Social indicators at every decision-making level will shape policies that truly work for vulnerable coastal communities. As countries prepare to advance Ocean Accounts and deliver on COP commitments spanning adaptation, local governance, health, jobs, education, justice, and human rights, integrating social data transforms these accounts from technical measurement tools into instruments of equity.